Jesus Was Angry at Death, and the Corruption of Sin That Made Death Necessary

I resume my study of John 11 from the last post. Jesus was not angry at Mary. He was certainly not angry at Lazarus for dying. Jesus was angry at something else. He was angry about the fact of Lazarus’ death, which ultimately goes back to why God imposed mortality on human beings in the first place. God exiled Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden so that human beings would not eat from the Tree of Life while in a corrupted state (Genesis 3:22 – 24). He did not want humans to simply immortalize human evil, at least before sending Jesus to undo the corruption of sin in his human nature, and offering his purified human nature back to us. Jesus’ anger is directed ultimately at human death, and through human death, the corruption of sin that made it necessary.

Can we be sure that the corruption of sin was the ultimate target of Jesus’ anger? A parallel to Mark’s Gospel is useful here. In the early part of his story, Mark maintains an opaque curtain that separates the audience from the characters. Whereas the characters hear Jesus’ words, we as the audience do not. We are watching a silent movie most of the time, looking at people’s facial expressions while we are cut off from most of the dialogue. But suddenly, Mark gives us a brief glimpse into Jesus himself. When the Pharisees opposed Jesus, even to the point of trying to find fault with Jesus when he healed a man’s crippled hand on the Sabbath, Mark tells us this: “After looking around at them with anger [ὀργῆς], grieved at their hardness of heart…” (Mark 3:5). “Hardness of heart” is an idiomatic expression from the Torah that meant the condition that a person could enter by making individual choices that worsen the inherited Adamic corruption of sin. Pharaoh, for example, worked himself into a state of “hardness of heart” (Exodus 7:13 – 14; 7:22; 8:15; 8:19; 8:32). Jesus said that his opponents had worked themselves into the same condition. Is it a coincidence that Jesus moved through the same emotions here as in John 11? Anger and grief?

Jesus was angry “with” Mary – not in the sense of being angry “at” her, but “with” her as “in agreement with her.” Jesus was angry in the same direction as Mary. And if Mary had not yet found the truest target for her anger, Jesus guided her to it. That is important for us because we can often misdirect our anger and grief. We can turn someone else – as in their personhood per se – into the target of our fury. That is, we can turn someone into a scapegoat, thinking that we can rid the world of that person to rid the world of human evil, forgetting that our struggle is not against flesh and blood per se (Ephesians 6:12), but against something else on a larger and deeper battlefield. Or we can turn our anger inward into self-hatred. Or we can place our anger into the wrong narrative so that we make God the author of the fall rather than our first human parents, give up in despair, or seek to escape the world into a Nirvana of nothingness. Here is where Jesus’ anger by the tomb of Lazarus becomes so important for us. He found the appropriate object for his human anger in agreement with divine anger: human death, and through it and behind it, the corruption of sin that is lodged in the human nature of every person.

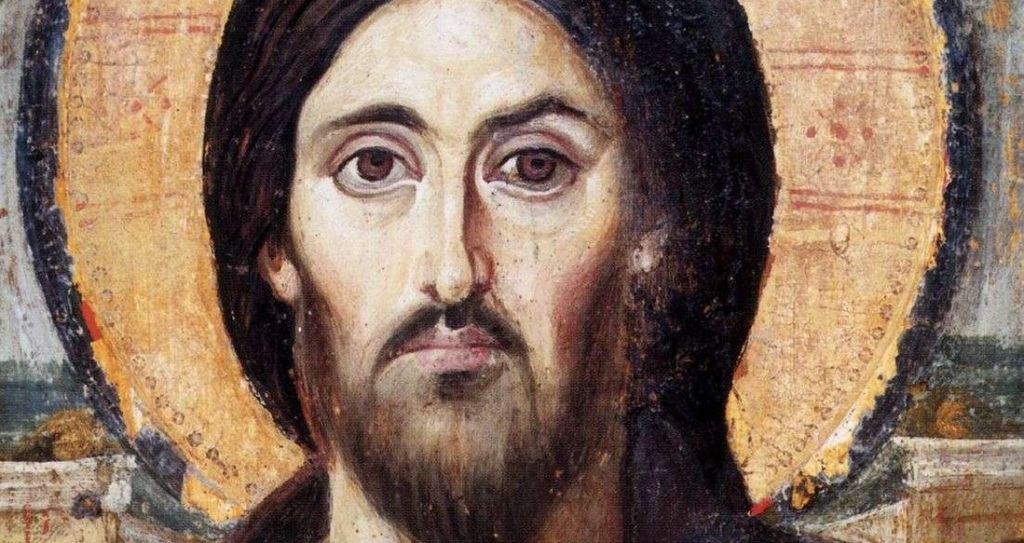

An influential bishop and theologian of the early church, Diadochos of Photiki (c.400 – c.486), wrote a reflection on John 11 demonstrating this interpretation, and making it practical. Diadochos was present at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 as the bishop of Photiki, a town in today’s northwestern Greece. His writings were collected in the Philokalia, a collection of valuable sayings from various Eastern Orthodox spiritual leaders. He recognizes the importance of anger properly harnessed, directed, and expressed under control:

“Becoming incensed usually spells trouble and confusion for the soul more than any other passion, yet there are times when it greatly benefits the soul. For when with inward calm we direct it against blasphemers or other sinners in order to induce them to mend their ways or at least feel some shame, we make our soul more gentle. In this way we put ourselves in harmony with the purposes of God’s justice and goodness. In addition, through becoming deeply angered by sin we often overcome weaknesses in our soul. Thus there is no doubt that if, when deeply depressed, we become indignant in spirit against the demon of corruption, this gives us the strength to despise even the presumptuousness of death.”[1]

Diadochos warns that anger can be a very unruly emotion. But pastorally, he views apathy as a bigger risk, which he calls a “weakness in our soul” that needs to be “overcome.” For he believes that anger has a proper stimulus and can be properly cultivated and directed.

As an example which was fairly common to use, Diadochos talks about becoming angry at these false teachers. In his day, heretical teachers wanted to pull Christian faith into Hellenistic presumptions that the body and the material world were too impure for God to personally touch. If victorious, those heresies would influence Christians to treat poverty and other bodily suffering as if they were not important. The heresies would knock the creation-friendly Old Testament out from under the New Testament as if we could love our neighbors without caring anything about their bodily experience, physical environment, and so on. Diadochos imagines that Christians engage with people in ways that are still “calm” and “gentle” outwardly. But inwardly, what overcomes that emotional inertia is “becoming incensed” in such a way that it “greatly benefits the soul” because it is “in harmony with . . . God’s justice and goodness.” For Diadochos, “becoming incensed” is compatible with “inward calm,” which is notable. He believes that we can feel multiple emotions at once. He might be describing a settled and unwavering conviction.

The ultimate target is “corruption” – the corruption of sin which has a demonic origin. To provide a foundation for teaching this, Diadochos examines Jesus in John 11. He writes:

“In order to make this clear, the Lord twice became indignant against death and troubled in spirit. And despite the fact that, untroubled, he could by a simple act of will do all that he wished, nonetheless when he restored Lazarus’ soul to his body he was indignant and troubled in spirit – which seems to me to show that becoming incensed in a controlled manner can be viewed as a weapon implanted in our nature by God when he creates us. If Eve had used this weapon against the serpent, she would not have been impelled by sensual desire. In my view, then, the person who in a spirit of devotion makes controlled use of the power of his anger will without doubt be judged more favorably than the one who . . . has never become incensed. The latter seems to have an inexperienced driver in charge of his emotions, while the former, always ready for action, drives the horses of virtue through the midst of the demonic host, guiding the four-horsed chariot of self-control in the fear of God.”[2]

Notice that Diadochos of Photiki calls Jesus “indignant” and “incensed in a controlled manner.” And he goes a step further to connect our anger and Jesus’. Jesus’ anger, this teacher says, was directed at the “corruption” of sin, which gave him “the strength to despise even the presumptuousness of death.” Diadochos interprets this anger as a potential “weapon” we can wield. Anger is a potential weapon with which we are equipped because we are created in the image of God.

For Diadochos, in other words, this anger is an experience of being truly human as God intended human beings to be. Jesus, therefore, was certainly truly human in the sense that he was recovering and restoring human nature through his own faithfulness. Anger in Jesus’ refined form would include a sense of moral revulsion towards any thought that would make us less devoted to God. If something would instill a fear in us of our own mortality so that we would prioritize our survival ahead of devotion to Jesus, then we would compromise with the corruption of sin, the archenemy within us. Against that temptation, Diadochos urges us, we must participate in Jesus’ human anger – we look to him, draw upon him, find inspiration in him.

Questions for Reflection

- What was Jesus’ anger and grief directed towards?

- What was Mary’s anger and grief directed towards?

- Is it possible to see in Mary’s anger and grief a miniature version of Jesus’?

Jesus’ Human Emotion Reveals Divine Emotion

In fact, since Jesus reveals the Father in fullness (John 1:17 – 18), Jesus’ human emotion here indicates that we can, and must, think something retrospectively about God. God had “divine emotion”[3] – if we can say that with appropriate caution – throughout the biblical story. From the moment God had to exile Adam and Eve from the garden to prevent them from immortalizing human evil (Genesis 3:22 – 24), God was emotionally affected in a way that corresponds to Jesus’ human emotion and how he manifested it. God preferred human mortality to sin immortalized, but that does not mean God ever took a detached view of human beings. This is almost certainly why the biblical narrative ascribes the human emotions of “sorrow” and “regret” to God early in the primordial narrative of Genesis 1 – 11, at the flood when God “was grieved in His heart” over the corruption in human “hearts.” That symmetry was surely not accidental, since those human beings had so corrupted themselves that “every intent of their hearts was only evil continually” (Genesis 6:5 – 6). These early biblical statements are surely meant to govern our reading of the rest of Scripture, and Jesus confirmed that at Bethany.

God was never emotionally detached from us, especially the evil that we inflict on one another. Moreover, when God took human life, we should not attribute to God the desire to simply inflict pain as if He just wanted to “get even” with us for his own “satisfaction,” as if God had a strictly retributive impulse in response to our wrongdoing and self-harm. Rather, God had to provide a community into which Jesus could be born and interpreted, and to protect the family of faith from attack and extermination, and therefore God had to take some human life. But God did so by gathering human souls in Sheol/Hades until Jesus could present himself to them that they, too, might regret their opposition and choose him (1 Peter 3:18 – 20; 4:6; Ephesians 4:9). Through and through, the ultimate and true targets of God’s anger have been human death – “the last enemy” (1 Corinthians 15:26) – and the thing in us that made our mortality necessary: the corruption of sin in our human nature (1 Corinthians 15:17; Romans 7:14 – 25). For death might be our last enemy, but it was not our first.

What Jesus did in Bethany was to express in emotion the truths of the great early church creeds. Jesus was homoousios – the same in essence – with the Father in his divinity and homoousios with us in his humanity. Jesus, as the Son of God on earth, showed us that God the Father in heaven, through the Son and by the Spirit, “covers” our fury and wailing, making even more sound and space for us.

In other words, when Jesus says that he discloses the Father’s character and love towards us, he was not only referring to raising Lazarus. Jesus was also referring to his human emotions as part of the revealing of God: “Did I not say to you that if you believe, you will see the glory of God?” (John 11:40). Jesus was not just showing people a miracle, however meaningful. Neither was he calling people to “believe” that he could reveal God to people every now and then when he did a miracle. Jesus revealed what God is like at every moment of his life. That included the fullness of his human responses to everyone and everything around him. Jesus revealed to Mary that this was God the Father’s own burden.

John’s Gospel encourages us to see Jesus’ anger and tears by the tomb of Lazarus as a “recapitulation” or “retelling of the story” of God’s own experience of exiling humanity from the garden of Eden. Demonstrating that adequately would be too long to do here. Suffice to say, though, that my assertion is connected to John’s overall goal of telling Jesus’ story as a “recapitulation” or “retelling” of God’s act of creation, from Genesis 1 and 2. John begins his narration of God’s new creation through Jesus with the phrase, “In the beginning” (John 1:1), just like Genesis 1 begins its narration of God’s original creation (Genesis 1:1). John structures his story around seven miracles, seven “I am” statements, and seven discourses, just like the creation hymn of Genesis 1:1 – 2:3 is structured around seven “days.” And John brings his story to a climactic high point when Jesus breathes his Holy Spirit into the disciples (John 20:22) just as God breathed life into Adam (Genesis 2:7).

The other Gospel writers (Matthew especially) encourage us to see how Jesus “recapitulated” or “retold” Israel’s covenant story – since Jesus is the true Israelite who succeeded where Israel failed in the covenant. Thus, Matthew emphasizes how Jesus was pursued with genocidal rage while an infant boy (Matthew 2:16 – 18) like Israel had been, came out of Egypt (2:15, 19 – 23) like Israel did, went through water (3:13 – 17) like Israel went through the Red Sea, then endured temptation in the wilderness (4:1 – 11) like Israel did, came to a mountain to receive and pass on God’s commands (5:1 – 7:28), and so on. The other Gospels stress Jesus’ humanity, to explain how Jesus fulfilled Israel’s side of the covenant with God — the human side.

John is distinct, though, because he is more clearly placing Jesus’ human journey into the role of God in creation, and God in covenant with Israel. Where Matthew, Mark, and Luke emphasize Jesus’ identity as truly human, truly Israelite, and truly Davidic, John complements them by emphasizing Jesus’ identity as truly divine. When we read, then, that Jesus loved Lazarus and his sisters, yet “let” Lazarus fall into death (John 11:1 – 15) in order to recover him from death, we are reading a miniature, a compressed reflection, of what it means for God to bring about a new creation. Thus, when we find Jesus’ anger and tears by the tomb of Lazarus, we are reading a miniature, a compressed reflection, for God to love humanity and yet “let” humanity die outside the garden (Genesis 3:1 – 24), and “let” Israel die in its own exile. In truth, God has felt like this since the fall.

Another fourth century Christian leader, Potamius of Lisbon, in what is now Portugal, wrote moving remarks about Jesus’ tears being God’s own tears, shed through Jesus’ human eyes out of love for us:

“God wept, moved by the tears of mortals, and although he was about to release Lazarus from the bond of death by the exercise of his power, he fulfilled the component of human affection with the comfort of his sympathetic tears. God wept, not because he learned that the young man had died before him but in order to moderate the sisters’ outpourings of grief. God wept, in order that God might do, with tears and compassion, what human beings do on behalf of their fellow human beings. God wept, because human nature had fallen to such an extent that, after being expelled from eternity, it had come to love the lower world. God wept, because those who could be immortal, the devil made mortal. God wept, because those whom he had rewarded with every benefit and had placed under his power, those who he had set in paradise, among flowers and lilies without any hardship, the devil, by teaching them to sin, exiled from almost every delight. God wept, because those who he had created innocent, the devil through his wickedness, caused to be found guilty.”[4]

That is a moving passage. As God, Jesus was “moved by the tears of mortals.” By weeping himself, God in Christ “fulfilled the component of human affection with the comfort of his sympathetic tears,” says Potamius. Jesus referred to his human emotions as part of revealing God: “Did I not say to you that if you believe, you will see the glory of God?” (John 11:40). Jesus was not just showing people a miracle, however meaningful that miracle was. Nor was he calling people to believe that he could reveal God every now and then when he did a miracle. Jesus revealed what God is like at every moment of his life. That included the fullness of his human responses to everyone and everything around him. Jesus revealed to Mary that this was God the Father’s own burden. “God wept.”

And the perception of God in Christ reached into the death of Lazarus, and through it, all the way back to the mortality required after the fall, when “human nature had fallen… [and] came to love the lower world.” This was the meaning of Jesus’ anger and tears.

Questions for Reflection

- Do you think it is possible to connect the Old Testament stories of God feeling angry or grieved to this moment when Jesus shows anger and grief? Why or why not?

- If Jesus as the Son reveals God the Father in fullness (John 1:1 – 3; Hebrews 1:1 – 3; Colossians 1:15 – 17; 2:9; etc.), then what do you make of Jesus’ human emotions?

Does God Really Care About Our Anger?

John Piper is one pastor and theologian who seems to disagree. Piper limits God’s showing of glory to Jesus’ raising of Lazarus. He therefore has little to say about Jesus’ human emotion. This is worth careful consideration, especially because he explains his interpretation of John 11 in his book, Bloodlines: Race, Cross, and the Christian. This intersection of Jesus’ emotion and pastoring people through racial injustice is significant in more ways than one. Piper says:

“Oh, how many people today – even Christians – would murmur at Jesus for callously letting Lazarus die and putting him and Mary and Martha and others through the pain and misery of those days. And if they saw that this was motivated by Jesus’s desire to magnify the glory of God, many would call this harsh or unloving. What this shows is how far above the glory of God most people value pain-free lives. For most people, love is whatever puts human value and human well-being at the center. So Jesus’s behavior is unintelligible to them.

“But let us not tell Jesus what love is. Let us not instruct him how he should love us and make us central. Let us learn from Jesus what love is and what our true well-being is. Love is doing whatever you need to do to help people see and savor the glory of God forever and ever.”[5]

It is standard Christian thinking about human sinfulness to acknowledge it is not good for us to be self-centered. So, on Piper’s account, to de-center us, God demands our worship. Piper maintains that this divine self-centeredness – God’s God-centeredness – constitutes “the glory of God.” But what makes it okay for God to be self-centered? Only that God is God. It is not okay for us, because we are not God. So Piper suggests.

Piper extends into his treatment of John 11 his theory of God’s own “God-centeredness,” which is closely intertwined with Piper’s commitment to Penal Substitutionary Atonement, which I will explore below. In my experience, and according to what I can discern about the logic of PSA, PSA adherents do not necessarily interpret John 11 in the same way John Piper does. However, I do wish to show that PSA does nothing to prevent Piper from interpreting John 11 this way. And several elements of PSA create a conceptual pull towards Piper’s interpretation of God.

Piper’s proposal has been amply criticized, though. Is it true that the only cure for our sinful narcissism is being confronted by a bigger Narcissist? Is that what God is like? Paul Louis Metzger, for one, points out that God cannot be self-centered, because God’s internal relations as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit make God the essence of loving other-centeredness. So while it is true that God demands our worship, it is not true that He does so to hoard praise and credit narcissistically. “Glory” does not mean praise and credit, and God does not want to prevent anyone else from having any. Quite the opposite. God wants everyone to be lovingly other-centered like He is in His internal relations, and to participate in those relations, which is a notable feature of John’s Gospel (John 15:9 – 10; 17:22 – 26). In fact, God wants us to prioritize receiving love from Him, and then sharing love from Him, with Him. So that we might do just that, God has utterly given Himself to us by His Son and His Spirit. Therefore, God calls us to worship Him not simply as “God” – which is a functional title (John 10:34 – 36; Psalm 82:6) – but as Father, Son, and Spirit (e.g. Matthew 28:19), because only by worshiping the Father, Son, and Spirit do we recognize, know, and participate in His loving other-centeredness, which benefits not only ourselves, but other people.

Metzger, continuing in this Trinitarian line of thinking, says he has reservations with the way Piper portrays God as monopolizing His own glory, as if glory were a commodity to be hoarded, as if God wanted to monopolize praise and credit as emotional commodities.[6] Scripture gives ample data to indicate that the word “glory” should not be defined that way at all. The meaning of the term “glory” is God revealing Himself, especially His love, and investing His people with His love and His very presence. God revealed Himself to Moses in a pillar of fire and light, and Moses’ face shone with divine light as a result of that encounter (Exodus 34). Jesus in his transfiguration far surpassed Moses when he manifested the divine light even more fully (Matthew 17:1 – 13; Mark 9:1 – 10; Luke 9:36 – 50). When we are joined to Jesus by his Spirit, and with the eyes of faith, we can see the “light” that shines from our faces, empowering us to grow by the Spirit of Christ from “glory to glory” (2 Corinthians 3:17). Paul sums up this theme by saying, “Christ in you” is “the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:27).

Piper’s proposal would diminish the emotional connectivity we have between each other and with God. To the Galatians, Paul said that the goal of the Christian life is that “Christ is formed in you” (Galatians 4:19). So what is the emotional intelligence of the version of Jesus that is being formed in Christians who listen to John Piper’s teaching? Metzger expresses his concern this way:

“By grounding his arguments in God’s glory-seeking, Piper’s arguments fail to offer an adequately God-modeled account of the affections. He thus leaves readers open to the inadequacies of hedonism’s self-centering motive that sustains pleasure as an end in itself.”[7]

Indeed, Metzger’s concern about having and showing the appropriate affections is well substantiated. Piper says nothing about Jesus’ way of expressing emotional solidarity with Mary, which would make Jesus rather insensitive as his own delay caused her to struggle and question his love.

According to Piper’s interpretation, Jesus might have regarded Mary as an emotional distraction to others, as if she were just calling attention to herself. Are we supposed to interpret Mary as trying to “hog” the attention while Jesus wanted to call attention to God’s power in raising Lazarus? If Christ thought nothing about the delay he himself undertook, and cared little to nothing for Mary’s anger and grief, because he intended to raise Lazarus and the “pragmatism” of the miracle was all that mattered, then Mary’s emotions were at best neutral, at worst sinful, and probably a distraction. If Jesus gave Mary no validity, appreciation, credit, or praise (“glory,” according to Piper) for feeling something he himself felt, too, because he was upset about being doubted and disbelieved, then Jesus might find nothing to praise in us when we mourn with anger and grief about the ravages of sin in the world. If Jesus monopolizes all credit or praise in any given situation, then Mary’s emotions were irrelevant – and inappropriate – to the whole situation.

Let us speak plainly. I have deep reservations about the emotional development that Piper’s interpretation of John 11 encourages. I believe that men, more so than women, would be drawn towards Piper’s interpretation of Jesus’ interaction with Mary. Why? Because a man can completely ignore the emotions of a woman on account of what he thinks Jesus did here. Why can he do this? Because that man believes his perspective and purpose is more important than her emotions. That man can therefore remain at an emotional distance, thinking to himself, “Jesus is the resurrection and the life.” His emotional immaturity, now wrapped in the garb of “objective truth,” shields him from the importance and validity of her suffering. It can become a building block of an emotional fortress that a man builds around himself, a fortress in which he privately licks his own wounds in his self-pity, while he tells himself that people are not as emotionally committed to the “missional purpose” that he has. And it is troubling that the solution for one person’s narcissism is to be placed “under” a Bigger Narcissist.

Further, this interpretation is what many evangelicals – especially today’s white evangelicals – would like to believe about their own position in American politics and the “culture war.” While other people suffer in many other ways, and grieve like Mary, we are in a completely different emotional space. We believe that we are like Jesus, holding forth the truth to people – truth not just about the gospel message but also on specific policies that privilege Christian faith. Of course, we interpret ourselves as well-meaning, so when we are rejected, we feel misunderstood and misinterpreted. And if we interpret Jesus as so emotionally separated from Mary, and so misunderstood and longsuffering, too, that Jesus becomes a projection of our political psychology, explicitly or implicitly. We justify our emotional disconnection from others by self-righteous self-pity. This interpretation does not build the kind of emotional connection and maturity in Christian disciples that we need to participate effectively with Jesus in his mission. I believe interpretations like Piper’s develop Christians towards emotional immaturity.

Piper’s reading of Scripture generates further habits of reading Scripture that do not develop emotional maturity and sensitivity. In terms of emotional development, the path of John Piper and the path of Diadochos of Photiki and Potamius of Lisbon could not be more different.

Questions for Reflection:

- If the goal of Christian ministry is for “Christ to be formed in you” (Galatians 4:19), then how would you explain why Jesus’ emotional life is so important?

- How does Jesus’ emotion encourage our own emotional development? Do you agree that it does?

- How does John Piper’s interpretation of Jesus’ anger and grief encourage a certain kind of emotional development? How does the interpretation held by Diadochos of Photiki and Potamius of Lisbon – important fourth century Christian leaders?

- Summarize in your own words the difference in the two interpretations of Jesus’ anger and grief.

- How does Jesus reveal God the Father? What is the argument that doing miracles alone reveals God? What is the argument for including Jesus’ words, emotions, and ways of relating to people?

- What is “the glory of God”? How might we define it?

[1] Diadochos of Photiki, On Spiritual Perfection 62. Quoted in Joel C. Elowski (editor) and Thomas C. Oden (general editor), Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament IVb: John 11 – 21 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2007), p.19 – 20.

[2] Ibid.

[3] I acknowledge the divine passibility-impassibility debate, and assert in brief that God’s nature as Triune and loving can be held to be unchanging and “impassible,” whereas God’s “divine emotions” (as it were) do appear to be dynamically responsive and “passible” within a range appropriate to God’s loving nature. See Terence E. Fretheim, The Suffering of God: An Old Testament Perspective (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1984) for an excellent treatment of Old Testament data, especially the movement of the prophets to bear not just the words of God but also the pathos, i.e. emotions of God. For an introduction to the question of how the early church wrestled with the terms they inherited, see Paul Gavrilyuk, The Suffering of the Impassible God: The Dialectics of Patristic Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). For a recent discussion, see Robert J. Matz and A. Chadwick Thornhill, Divine Impassibility: Four Views on God’s Emotions and Suffering (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2019) especially the position of Thomas Jay Oord.

[4] Potamius of Lisbon, On Lazarus, edited by Joel C. Elowski and Thomas C. Oden, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament IVb: John 11 – 21 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2007), p.21.

[5] John Piper, Bloodlines: Race, Cross, and the Christian (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Publishing, 2011), p.251.

[6] Paul Louis Metzger, “The Halfway House of Hedonism: Potential and Problems in John Piper’s Desiring God,” CRUX: A Quarterly Journal of Christian Thought and Opinion Published by Regent College, Winter 2005/Vol.41, No.4.

[7] Metzger, p.21, emphasis mine. Metzger’s full quote is as follows, and worth much reflection:

“In glory-of-God models, however framed,… God’s chief end is to glorify himself and to be glorified by others. But this…is self-love, consumption, narcissism. In John’s Gospel, on the other hand, one finds in the relationship of the Father and Son what [Eastern Orthodox theologian Timothy] Ware calls “an unceasing movement of mutual love,” the love of persons… And so it is that the Christian God is not an Absolute individual in isolation, but a community of persons in selfless, abiding communion. Thus, the supreme glory each of the divine persons receives in the joyful communion of love is the fruit of each person’s loving purpose, not the focal pursuit… By grounding his arguments in God’s glory-seeking, Piper’s arguments fail to offer an adequately God-modeled account of the affections. He thus leaves readers open to the inadequacies of hedonism’s self-centering motive that sustains pleasure as an end in itself. By not recognizing love as the focus and glory as the fruit of the Trinitarian life, Piper’s arguments ultimately, and ironically, fail to be sufficiently free from the duty-based models he seeks to leave behind.”

2 Comments Add yours