The Posture of the Father Towards Jesus and Towards Us

As a child, I was afraid that I would make my favorite sports team lose by watching them play on TV. I had a fear: Was the cosmos against me, even in trivial ways like that?

Similarly, at times, we feel like the universe is against us somehow. When we don’t get a parking space. When a loved one gets cancer.

And when we stop to recognize that the universe will one day become cold, dark, and dead, we wonder. Maybe life is a short, brief tease in a cosmos that promises to turn against us and swallow us up in death.

Whether it’s rational or not, it’s easy to project these nagging thoughts onto God the Father.

What is the demeanor and posture of God the Father towards us? Is there anything in him that would make him turn against us, or away from us? And what is the Father’s demeanor and posture towards Jesus at his hour of deepest need? Did he turn against or away from Jesus? Those questions are inseparably related. In the midst of all our anxieties, suspicions, and insecurities, we must address this – one of the most significant of all emotional and theological questions.

How Penal Substitution Portrays the Father

John Stott, in his treatment of Jesus’ cry from the cross, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me,’ affirms that God does abandon and forsake us indeed, through the experience of Jesus himself. Stott’s response to this insecurity about God the Father is to take comfort in the suggestion that Jesus experienced that, too. It is unclear to me why anyone would be comforted by that idea.

In what is called the penal substitutionary atonement theory, the Father turning against and/or away from the Son is a staple belief. We deserve a penalty for the guilt of our sin, however big or small, because God is an infinite being against whom any offenses deserves an infinite penalty. But Jesus substitutes himself in for us to take that penalty. I believe this theory of penal substitutionary atonement misinterprets the demeanor of God the Father. Stott, a representative of that theory, says:

‘In the darkness, however, he was absolutely alone, being now also God-forsaken… an actual and dreadful separation took place between the Father and the Son; it was due to our sins and their just reward; and Jesus expressed this horror of great darkness, this God-forsakenness, by quoting the only verse of Scripture which accurately described it, and which he had perfectly fulfilled, namely, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’[1]

However, Stott simultaneously asserts that the Father did not forsake the Son. This is curious:

‘The… God-forsakenness of Jesus on the cross must be balanced with such an equally biblical assertion as ‘God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ.’ C.E.B. Cranfield is right to emphasize both the truth that Jesus experienced ‘not merely a felt, but a real, abandonment by his Father’ and ‘the paradox that, while this God-forsakenness was utterly real, the unity of the Blessed Trinity was even then unbroken.’[2]

This results in a very mixed, even schizophrenic, presentation of God the Father. I dare say, this understanding does little to nothing in addressing our doubts about the character, demeanor, and disposition of God the Father.

The Father Was Always Well-Pleased by the Son, and With the Son

A core staple of historic, orthodox reflection on the Trinity – for example, from the pen of Athanasius of Alexandria, and the church leaders who convened at the Council of Nicaea in 325 – is that the Father and Son have enjoyed an unbroken relationship of mutual indwelling and love. This core belief flows out of statements Jesus made about the Father loving him and indwelling him, primarily from John’s Gospel (Jn.14:6 – 11; 15:9 – 10; 16:32; 17:21 – 26). The Nicene Creed of 325, taking note of those statements in the battle with Arianism(s), declares that the Son is ‘same in essence’ (homoousion) and ‘from the essence’ (ek tis ousia) of the Father, which has profound implications for the unity of Father and Son.

However, I have not yet explained the Father-Son relation by analyzing one of the Synoptic Gospels per se, especially Matthew or Mark, wherein we find the cry of Jesus, ‘My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?’ In the past few posts, I have argued point by point against the penal substitutionary interpretation of Jesus’ cry from the cross, which requires that Jesus bore the infinite retributive justice of God. To the contrary, that is not at all what a closer examination of the text upholds. David, the original human author of Psalm 22, was not expressing being vertically forsaken by God, as if God had personally turned against or away from him. Instead, he was registering a complaint with God about feeling horizontally forsaken to his enemies. God was still assuring David even as he composed Psalm 22 that He was listening, protecting, caring, and responding in covenantal lovingkindness. In fact, David, as the rightful king anointed by the Holy Spirit, and as a prophet inspired by the Holy Spirit who composed Psalm 22, could not have been God-forsaken in a vertical sense because that would jeopardize the divinity of the Holy Spirit. Therefore, God was assuring David through the Spirit-anointing that He had not abandoned David, or in any way departed from Him.

I also examined the way Jesus retold David’s story from David’s pre-enthronement period. Both by word and by deed, by direct verbal quotation and by allusion through re-enactment, Jesus made the case for himself being the true heir of David: If David was initially rejected and suffered before being enthroned, why not the Son of David who is the greater David? I paid special attention to how Jesus deployed Psalm 22 from the cross. He did not seem to be referring to his own emotional state, given the honor-shame culture which he inhabited. Rather, he seemed to quote it against his detractors, who had already quoted Psalm 22 whether they intended to or not. Their mockery took the exact words and erroneous judgment of those who mocked the early David. Jesus’ utterance of Psalm 22:1, therefore, served as part of Jesus’ argument that he was indeed the messianic heir of David whose story had to resemble David’s story, because he was the greater David. Jesus retells our stories, but succeeds where we failed.

I will now look at the three times in Matthew’s Gospel when the Father says that he is ‘well-pleased’ with the Son. The achievements and commitments Jesus made during those three episodes will inform the implicit demeanor of the Father towards him during the crucifixion experience. Not only that, but the relationship between the Father and Jesus disclosed beforehand will require a conclusion: the Father could not have turned against or away from Jesus in any sense while he hung on the cross.

The Father Pleased by Jesus’ Public Commitment to Cleanse Human Nature: Matthew 3:13 – 4:11

‘This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased.’ (Matthew 3:17)

The first time God the Father speaks, he says these words. Why? We can identify two main reasons. First, the Father summarized Jesus’ life up to that point. The Father’s word of blessing and love indicates that Jesus had never sinned before. Jesus was absolutely blameless.

Second, the Father’s blessing and love empowered Jesus henceforth for the public role on which he was embarking. Jesus was publicly declaring his claim on the throne of his father David. The Father indicates that he fully approved of Jesus’ shifting from quiet private citizen, as it were, to messianic king. In this sense, the Father’s word must be heard as a quotation of the coronation psalm of the kings of Judah: Psalm 2.

But the latter aspect, Jesus’ public role as king, was built on the foundation of the former, Jesus’ basic role as a human being. Jesus had to continue being victorious over the corruption of sin. As a human being dependent on the Spirit, Jesus was going to conquer the temptation of sin and cleanse his human nature from the corruption that lay deep within it. Thus, Jesus came to be baptized, which involved the confession of sin and need for cleansing. John the Baptist was surprised, since he assumed the messiah would not need to do such a thing. But Jesus apparently confessed the sinfulness of his humanity. He did not confess personal guilt for committing a sinful act in deed, word, thought, or emotion – for in that regard, he was sinless. In effect, he ‘outed’ every human being. The problem of sinfulness goes more deeply than anyone cares to admit. By confessing the sinfulness of his own humanity, Jesus confessed the sinfulness of each one of us.

Jesus also publicly committed to taking that sinfulness all the way to its death, despite the added pressures and stresses of identifying himself as the promised heir of David, and gathering a group of followers in a tense, hostile environment. The rite of baptism represented a commitment to die and be raised again. Therefore, Jesus said he had another baptism to undergo: actual death and resurrection, indicated directly by Luke (Lk.12:50), and by Matthew by other means. Jesus demonstrated his commitment to radically excise that sinfulness by never giving into the temptations in the wilderness (Mt.4:1 – 11). In light of this public commitment, the Father declared that Jesus was his beloved Son.

I believe Jesus can be thought of as etching and inscribing the identity of ‘beloved child of God’ into his humanity. The Hebrew Scriptures, notably the Proverbs and Jeremiah, regarded the human heart as a tablet on which the human worshiper of God needed to write the commands of God (Prov.1:23; 2:10; 3:3; 6:21; 7:3). Unfortunately, the script of sinfulness was already there in some way (Jer.17:1 – 10), surely in various degrees across people, and needed to be undone. God therefore needed to rewrite His law upon the tablets of human hearts in the new covenant (Jer.31:31 – 34). Matthew called attention to Jeremiah’s prophecy and hope at the start of Jesus’ human life, quoting Jeremiah’s mournful commentary on Israel’s exile (Jer.31:15) when Israel was vulnerable to the murderous Herod as Herod sought to kill the infant Jesus (Mt.2:17 – 18). But if Jeremiah’s hope was for a new covenant, which inscribed divine law on human hearts in a new and deeper way than Sinai could, we are surely invited to see Jesus as enacting that new covenant, on a mountain like Sinai, and with divine law addressing the human heart at last. In the wilderness temptation, the devil wanted to trick Jesus into redefining the meaning of ‘Son of God’ into something else. Jesus responded by saying, first, that he must live on every word that comes from the mouth of God. The last word Jesus had heard was, ‘This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased.’ No doubt that blessing of love from the Father continued to resonate quietly in his human heart and mind. He was taking what he had heard from his Father, and engraving the Father’s blessing of love into his human nature, which had a strange resistance and rebellion within it.

The Father Pleased by Jesus’ Revealing Him: Matthew 11:25 – 12:21

‘Behold, My Servant whom I have chosen; My beloved in whom My soul is well-pleased’ (Matthew 12:18)

Jesus gathered people who had similarly been baptized by John the Baptist, which signified a personal Exodus-Red Sea experience. He drew them together and brought them to a mountain, where he gave his followers the new law of the heart (Mt.5:1 – 7:29), echoing God at Mount Sinai but also fulfilling Jeremiah’s long hoped-for vision of divine writing onto the tablets of human hearts (Jer.31:31 – 34). Jesus uttered ten declarations that delivered people from disease, death, and the demonic (Mt.8:1 – 9:35), echoing the ten words on Egypt which freed Israel from bondage, and also the ten commandments, which were meant to help Israel come free from their sinfulness, though their flesh was too weak for this to be effectual (Rom.8:3). Then Jesus sent out his disciples to claim people, in a new type of conquest and inheritance, looking for ‘people of peace’ (Mt.9:36 – 11:1), much like God sent the Israelites out to claim the land as their inheritance and found Rahab and her household. By doing all this, Jesus was recapitulating the role of God in Israel’s history. He was making a claim to be divine.

But Jesus appeared – miracles and manner of speech aside – to be a mere man. How could this mere man claim to be divine? To further refine his assertion, Jesus then made this astounding claim to uniquely know and reveal the Father:

25 ‘I praise You, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that You have hidden these things from the wise and intelligent and have revealed them to infants. 26 Yes, Father, for this way was well-pleasing in Your sight. 27 All things have been handed over to me by my Father; and no one knows the Son except the Father; nor does anyone know the Father except the Son, and anyone to whom the Son wills to reveal Him.’ (Matthew 11:25 – 27)

This statement has been called ‘the bolt from the Johannine sky’ for its resemblance to the Father-Son statements contained in John’s Gospel. Jesus’ next claim, to offer true ‘sabbath rest’ to those who come to him (Mt.11:28 – 30), only took his claim one step further. Who else could grant ‘rest’ but God who ordained it first in creation?

When challenged about these claims, Jesus then said, ‘Something greater than the temple is here’ (Mt.12:6). In effect, Jesus drew on the Jewish historic institution of the temple to denote how God located His tangible presence in one and only one location. Now, Jesus was claiming to be that location, in a human mode of being. Furthermore, the temple fits as a template for Jesus as housing and revealing the divine. This would retrospectively buttress Jesus’ implicit claim to be divine, given his past activities which drew from the Mosaic era of Israel’s history. From a roughly chronological perspective of Israel’s history, which Jesus was retelling (recapitulating), he segues into the Davidic era, which was dominated by the physical temple building in Jerusalem.

Before moving on to Jesus’ retelling of Israel’s Davidic era, however, mention must be made of the quotation from the prophet Isaiah. Matthew comments on Jesus’ activity and claims by quoting Isaiah 42:1 – 4. This messianic ‘Servant Song’ speaks of the Isaianic ‘Servant’ who is the ‘chosen one’ who stands in for the ‘chosen people,’ because Israel had failed in their vocation to be a light to the nations. The scope of the mission and kingdom of the messiah is, as Isaiah reminds us, ‘the Gentiles,’ and not just Israel. And in connection with this vision, God says that the ‘Servant’ is ‘My beloved.’ While questions about the meaning of Isaiah 53 need to be addressed as well, which I have done elsewhere, there is no indication here that God pours out divine retributive justice on the Servant instead of Israel, or makes the Servant face a form of divine abandonment. There is only a reminder that the Father said, ‘This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased.’

The Father Pleased by Jesus Establishing His Kingdom: Matthew 17:1 – 13

‘This is My beloved Son, with whom I am well-pleased; listen to him!’ (Matthew 17:5)

In the fourth section of Matthew’s Gospel (Mt.14:1 – 19:1), Jesus reinforced his identity as both ‘king’ and ‘temple,’ retelling the pre-enthronement period of David’s life. Jesus supplied bread abundantly, twice: once to Jews (Mt.14:13 – 21) and once to Gentiles (Mt.15:29 – 39). These were Davidic actions with temple symbolism. Sandwiched between the two feedings, Jesus critiqued the existing physical temple building, while referencing the existing problem of human evil in the heart which needed to be resolved if God were going to dwell in human beings, implying that he would solve that problem (Mt.15:1 – 20). He demonstrated his concern for a Canaanite woman and welcomed her into the family of God (Mt.15:21 – 28), since a universal human problem necessitated a universal invitation to join Jesus’ movement and God’s family now organized around Jesus. Jesus then drew out from the disciples, notably Simon Peter, a confession of his messianic title (Mt.16:1 – 28). Jesus then goes to be transfigured (Mt.17:1 – 13).

As the temple was on Mount Zion, Jesus was similarly on Mount Tabor. As God’s presence descended on the temple as a cloud of glory, Jesus is suffused and surrounded by a cloud of glory. As God appeared in light and glory, Jesus appeared to his disciples radiant of face and garment. Whatever the exact meaning of the appearance of Moses and Elijah on the mountain with Jesus, it is striking that both men encountered God before on a mountain. Moses met God on Mount Horeb with awe-inspiring natural phenomena, and then beheld some manifestation of God which made his own face shine (Ex.34:1 – 35). And Elijah met God on Mount Horeb with awe-inspiring natural phenomena, and then a soft whisper (1 Ki.19:8 – 12). Also, Moses and Elijah were important in calling people away from a false authority to God’s authority: Moses represented God and God’s covenant when God brought Israel out of the authority of Pharaoh; Elijah represented God and God’s covenant when God brought Northern Israelites out of the authority of the non-Davidic king in the North. Jesus represented God and God’s covenant to gather people out of the authority of all other rulers. Moreover, both Moses and Elijah anointed successors, Joshua and Elisha respectively, to lead the mission to claim God’s inheritance. Now, to support Jesus’ mission to reclaim God’s inheritance of people, come the great predecessors. Moses and Elijah come to anoint their true successor, the greater Joshua and the greater Elisha. And Jesus is affirmed, not only through Moses and Elijah, but most importantly, by the voice of God the Father.

The Father’s voice comes once more to authenticate Jesus. By this point in time, although his mission is not yet complete, Jesus has demonstrated that he can be victorious over temptation, inwardly, and therefore establish the messianic kingdom, outwardly. Once again the relationship between the dual aspects of his mission is highlighted.

The story of the demon-possessed boy (Mt.17:14 – 23) seems to serve a few functions related to Jesus’ humanity and mission. First, the story suggests that the nine disciples (those other than Peter, James, and John) who were not with Jesus on the mountain encountered a limitation to their spiritual power. This limitation is connected to not knowing about or understanding Jesus’ transfiguration, and, by extension, Jesus’ coming death and resurrection. God will connect more spiritual power over the demonic with Jesus’ resurrection and enthronement.

Second, Jesus says that the divine presence and power demonstrated on ‘the mountain’ of transfiguration can be ‘move[d] from here to there’ (Mt.17:20). This cryptic remark can be connected to Jesus’ temple-like actions, as well as his later remark just outside of Jerusalem when he effectively says that the disciples will ‘move’ the presence of God from the Jerusalem temple to the realm of the Gentiles, where they will go in Christian mission (Mt.21:21 – 22; the ‘sea’ to which Jesus refers is a Danielic term for the realm of the Gentiles – the place from which the beastly empires arise). The disciples will take the presence of Jesus – transfigured and resurrected – with them in mission to the world.

Third, Jesus saw a parallel between the boy and himself. The demons treated the boy violently. And Jesus foresaw his treatment at ‘the hands of men’ violently, to be killed and raised again (Mt.17:22 – 23). This episode matters for our understanding of the atonement. Jesus did not indicate, or even remotely suggest, that God the Father would treat him with violence in any form. The ill-treatment Jesus would endure comes from men.

Did It Please the Father to Punish the Son? Jesus’ Struggle in Gethsemane: Matthew 26:36 – 46

‘My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me; yet not as I will, but as you will.’ (Matthew 26:39)

The Father’s voice is curiously absent from the story of Jesus during his temptation in Gethsemane, trial, and crucifixion. What are we meant to infer from this?

The Cup of God’s Wrath

Jesus referred to the ‘cup’ of the cross as physical death. We know this because Jesus said the disciples would drink from the same ‘cup’ from which he was going to drink:

22 But Jesus answered, ‘You do not know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I am about to drink?’ They said to him, ‘We are able.’ 23 He said to them, ‘My cup you shall drink…’ (Matthew 20:22 – 23)

In other words, the disciples will face their own deaths by martyrdom in their own ways. Since there is no other distinct ‘cup’ introduced between this conversation and Gethsemane and the cross, we are left to conclude that Jesus was simply referring to death by martyrdom. The ‘cup’ is physical death.

Much more has been made of this ‘cup’ of Gethsemane by penal substitution advocates. John Stott, for instance, believes there must have been quite a different and unique ‘cup’ for Jesus that his disciples did not drink, despite Jesus saying quite the contrary. Stott points out that neither Socrates nor Christian martyrs nor people dying for other causes dreaded death as much as Jesus.[3] What then explains the terrible agony that Jesus felt in Gethsemane? Was he uniquely cowardly? Surely not. How then can we explain the ‘cup’ referred to at Gethsemane simply as ‘death?’ Why did Jesus dread death so much?

Stott believes that there was a measure of divine wrath that invisibly passed onto Jesus, which he ‘drank.’ He concatenates references to a ‘cup’ of God’s wrath from the Old Testament.[4] God handed the disobedient and rebellious a ‘cup’ of ruin, desolation, etc. until they drink it dry (Ps.75:8; Isa.51:17 – 22; Jer.25:15 – 29; 49:12; Ezk.23:32 – 34; Hab.2:16; Rev.14:10; 16:1ff and 18:6). The ‘cup’ to be drunk always refers to a historical experience that had a terminus; hence the metaphorical use of the idea of drinking a cup dry.

But most of these references are related only semantically; they simply share a common metaphor to describe varied historical experiences.

Moreover, God had already ‘poured out’ His wrath in the Old Testament. So what divine wrath was leftover for Jesus to drink? Prior to Jesus, God had to protect Israel for Jesus’ sake, and therefore had to judge the Gentile nations roundabout Israel for the harm they dealt Israel. This was true of the generation of Noah, which menaced the family of Noah, the last family of faith, with violence (Gen.6:5 – 6); if faith was extinguished from the earth, there would be no family to raise Jesus, so God had to protect Noah and family. The same could be said for Sodom and Gomorrah, rescued once by Abraham (Gen.14) yet deeply hostile to Lot and family, and any new settlers to the land (Gen.19).

Furthermore, God had already ‘poured out’ His wrath upon Israel for their rebellion against Him. He caused a few supernatural events, but otherwise, God simply declared that the Gentile enemies who perceived concentrated wealth in Jerusalem – itself an act of disobedience against God (Dt.17:16 – 17) – and concentrated power there were drawn in by Israel’s leaders’ own disobedience (e.g. Isa.38 – 39). The nations that menaced Israel would do them harm, and ultimately take them into exile. So, when God addressed Jerusalem, He said, poetically, that Jerusalem had already suffered double the punishment for all her sins (Isa.40:1). He said that the nations like Babylon, which had been involved in Jerusalem’s overthrow, exceeded what God intended and would be punished (Zech.1:12 – 17) by successive empires, each being toppled by the next (Dan.7 – 12). The author of Hebrews summarizes salvation history prior to Jesus by saying that ‘every transgression and disobedience received a just penalty’ (Heb.2:2) already.

That includes human death: Death is the severe mercy that God imposed on human beings as the alternative to allowing human beings to immortalize the corruption of sin inside us, if we could eat from the tree of life (Gen.3:22 – 24). God’s loving hand was forced by Adam and Eve to close access to the garden. It was a consequence of love, and even a punishment, yes, but intrinsic to the sin, not extrinsic to it and arbitrarily added on. After all, God said, ‘You will die,’ not, ‘I will kill you.’

What divine wrath, then, was still remaining? Does the ‘cup’ of God’s wrath refer to the future judgment of a penal hell, conceived of as a prison from which people desire to escape and be with God, yet God says ‘no’? Did Jesus get a foretaste of this? I do not think so. For instance, the motif of fire, which characterizes hell, and is so often taken to be strictly retributive and punitive, begins positively in every biblical book in which it appears.[5]

The phrase Matthew often uses, ‘fire and darkness,’ comes from Israel’s refusal to come up Mount Sinai to meet with God. Moses, by contrast, went up to see and meet with God, and his face shone (Ex.34). Moses said: ‘You came near and stood at the foot of the mountain, and the mountain burned with fire to the very heart of the heavens: darkness, cloud and thick gloom…’ I was standing between the LORD and you at that time, to declare to you the word of the LORD; for you were afraid because of the fire and did not go up the mountain (Dt.4:11; 5:5). Fire and darkness are literary motifs related to Israel’s failure at Mount Sinai. They said, ‘No’ to God’s invitation to come higher up and further in, and remained on the outside of God’s special presence instead.[6]

There is no biblical basis to assume that God must inflict death on us when we sin, because we inflict death on ourselves; sin itself is a movement towards death. Read Romans 6:23 in context, and you’ll see that sin, not God, pays out wages (results) called ‘death.’ There is no biblical basis, therefore, to assume that God has an attribute that we could call ‘divine retributive justice,’ where any offense against God’s holiness calls for infinite wrath, on the supposed grounds that God is an infinite being. Such a claim collapses all sins – trivial and monstrous – into one category, making ‘stealing paper from the office’ as morally punishable in an infinite torture chamber as ‘masterminding the Holocaust.’ And ‘retributive justice’ as an attribute cannot even be logically connected to the conviction that God is love (1 Jn.4:8) in His very nature. If God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit from all eternity, even before the Triune God made anything, then all activities of God in relation to the creation must flow out of His love, and be expressions of His love.[7] Thus, God’s wrath must be an expression of His love: like the wrath of a surgeon against the cancerous sin in our bodies, which serves the love of the surgeon for us as persons because he wants everything that harms us out of us.

The Reason for Jesus’ Agony at Gethsemane

So if Jesus was not going to endure a hidden, invisible torture of divine retribution, then why did he tremble so much at the prospect of the cross? Because losing human life was so unnatural from the standpoint of God’s original design for his creation. Maximus the Confessor (c.580 – 662 AD), the brilliant Greek Byzantine theologian and monk who lost his tongue and right hand opposing the heresy called monothelitism, was the first to formally write about this. A representative of Catholic scholars who have a renewed appreciation for the Greek East, Edward T. Oakes, S.J., summarizes Maximus’ position in this way:

‘In prior centuries, pagan philosophers often invidiously pointed to Christ’s agony in the Garden as a sign of weakness before death, in pointed contrast to Socrates, who faced death serenely. Prior to Maximus, the accusation often stung; but with his more robust and anti-Socratic defense of the independent faculty of the will, the Confessor was able to turn the tables on the Platonists by showing how the human will by nature seeks the good of life and thus flinches from death, especially voluntary death. Yet this natural reluctance to die, in the case of Jesus, does not result in disobedience – not because his divine will overwhelmed his human will, but because the human will always sought obedience – and did obey in a constant human act.’[8]

Almost certainly, Jesus’ experience of death was a heightened version of ours. We who are ordinary humans experience a loss of our senses, a slow-down of our mind, and a dullness of soul the closer our bodies get to physical death. It is possible that Jesus, in his human soul by contrast, did not lose any clarity at all. It is likely that Jesus’ human soul, aided by divine awareness, was acutely more aware of all that would happen to his human body.

I wish, however, to take this basic insight one step further. I am not so sure that explaining death simply as a violation of God’s intended order is a sufficient reason to explain Jesus’ deep emotion. I believe we can glimpse something else. Why did Jesus tremble in agony at Gethsemane? Because of love. Jesus was the creator of all things (Jn.1:1 – 3; Rom.11:33 – 36; 1 Cor.8:6; Col.1:15 – 17; etc.), who loved all beings, especially human beings, and that included his own human body. Jesus in Gethsemane revealed the true extent of God’s divine horror and revulsion at the death of any human being.

Bethany and Gethsemane

The ‘Johannine Gethsemane’ at Bethany clarifies that for us. When Jesus wept and felt distress at the tomb of Lazarus, he demonstrated an emotion denoted by a word used to describe horses snorting in anger: enebrimēsato / ἐνεβριμήσατο (Jn.11:33). Translating this ‘he was deeply moved’ (NASB), ‘he groaned in the spirit’ (KJV, ASV), ‘he was deeply disturbed’ (CEB), ‘he was deeply moved in his spirit’ (ESV), and ‘he was greatly disturbed in spirit’ (NRSV) is too mild and too vague. NLT and The Message translate this phrase better: ‘a deep anger welled up within him,’ with NLT adding, ‘and he was deeply troubled.’ CEV renders it, ‘he was terribly upset.’ JUB offers, ‘he became enraged in the Spirit and stirred himself up.’

Although it lies beyond the scope of this essay here, I believe John wrote his Gospel to help us interpret Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Matthew, Mark, and Luke told the story of Jesus to highlight how Jesus fulfilled the story and prophetic hopes of the Hebrew Scriptures. John did not leave that concern behind, but additionally wrote to engage with the gnostic heresy and the Hellenistic mindset which strictly divided heaven and earth, soul and body. The gnostic mindset also separated divinity from humanity in Jesus. This was why the early church drew so heavily upon John’s Gospel in their struggle against heresy – it was John’s actual intent. John included Jesus’ own description of his inner life with the Father (Jn.5:19 – 30; 10:14 – 18, 29 – 30; 14:9 – 11, 23 – 24; 15:8 – 10; 16:32; 17:20 – 26), to insist on the oneness and mutual indwelling between the Father and the Son.

Therefore, the nature of Jesus’ agonizing struggle in Gethsemane must be brought into close dialogue with Jesus’ angry and troubled emotion at Bethany. Jesus felt that emotion not for himself, but for Lazarus, and for the sake of Lazarus and the community gathered around his tomb. He was angry with the devastating cost of death, the fact of death itself, and the corruption of sin which made death necessary, reluctantly so from God’s perspective. Jesus’ emotion at Bethany was the manifestation of focused indignation towards death as ‘the last enemy,’ as Paul says (1 Cor.15:26), and sinfulness as its deeper provocation.

At Bethany and at Gethsemane, as always, the Son revealed the Father perfectly (Heb.1:1 – 3; Mt.11:25 – 27; Jn.1:1 – 3, 17 – 18; 14:9 – 11; Col.2:9). This conviction means that Jesus’ human emotions reflected something we might call, with caution, ‘divine emotion.’ John presents Jesus as recapitulating the role of God in creation. In this frame, Jesus is God incarnate – or rather, the Son-Word of God incarnate – forging a new creation and breathing life into a new humanity. This is seen in the massive literary allusion John makes through his narrative to Genesis 1. John jogs our memory of Genesis 1:1 through his own restatement, ‘In the beginning’ (Jn.1:1). He reminds us of the seven days of creation in Genesis 1 through a series of seven miracles,[9] seven ‘I am’ statements,[10] and seven discourses of Jesus.[11] He reminds us of the garden of Eden in Genesis 2 by noting the location of Jesus’ tomb in a garden (Jn.19:41 – 42) and even including the detail that Jesus was mistaken for a gardener (Jn.20:15). He reminds us that God breathed new life into Adam (Gen.2:7) by including Jesus breathing the Holy Spirit into the disciples (Jn.20:22). John portrays Jesus as recapitulating his creative role as the eternal Son. Jesus is God and the Son-Word of God. He is bringing forth a new humanity and new creation. As such, he represents the Father perfectly, even in his human emotions. Especially in Jesus’ seventh, and greatest, miracle – when Jesus includes his emotions as part of the disclosure of God: ‘Did I not say to you that if you believe, you will see the glory of God?’ (Jn.11:40).

Yes, I acknowledge the divine passibility-impassibility debate, and assert in brief that God’s nature as Triune and loving can be held to be unchanging and impassible, whereas God’s ‘divine emotions’ (as it were) do appear to be dynamically responsive within a range appropriate to God’s loving nature. The upshot of framing Jesus’ emotions in this way is that Jesus’ human emotion of agony and anguish are the manifestation of a divine love to wish life and not suffering and death on anyone. Jesus’ emotion does not simply reflect a natural human will to live, but a divine will to bless and give life. Socrates regarded his body to be an encumbrance, and so had comparatively less love for it, not to mention awareness of it as the hemlock dulled his soul’s senses. Jesus, however, did not regard his body as an encumbrance, but as beloved. So the agony and anguish of Jesus lies not in how painful or terrible death per se could be, but in who was willing the dying. Again, Jesus’ human experience of death might have been qualitatively different from ours because of his acute awareness, but the key to understanding Gethsemane lies in how divinely and truly humanely loving Jesus was towards his own humanity as he was towards others.

Not What is Death, But Who Willed the Dying

Jesus trembled at Gethsemane because he looked ahead to the cross and agonized over the fact that he had to put something to death that he cherished and loved: his humanity, because he loved it as he loved Lazarus, Mary, Martha, and all other human beings. The eternal Son’s now incarnate humanity was not a mere instrument, but a treasured ontological reality over which, and within which, he said, ‘It is good’ as he did in the original creation. To put his humanity to death was to surrender something precious, as precious as any child would be to a caring father or mother, as cherished as a wife would be to her devoted husband.

So if there was a conflict of divine commitments and loves (but not a conflict of divine ‘attributes’ per se), then we can see that conflict in Jesus at Gethsemane. But it was a conflict between loves, and within divine love. It was not a conflict between love and retributive justice (as in penal substitution). The Father loved the Son’s humanity, and the Son manifested the Father’s love for humanity by cherishing his own humanity, as it was, in that moment, as well as his personal union with his human nature. Jesus speaks of the Father’s love for his humanity and himself when he says the Father was willing to put ‘at his disposal more than twelve legions of angels’ (Mt.26:53). The Father did not have a casual or punitive attitude towards Jesus’ humanity. The human desires of Jesus, reflecting the original image-of-God nature intended from creation, trembled at the prospect of death because that agony was also ultimately rooted in the Father’s love as well.

Jesus’ emotion even suggests that we can retrospectively ‘read back’ divine emotion of this sort onto God from earlier parts of the biblical story. From the moment God had to exile Adam and Eve from the garden to prevent them from immortalizing human evil (Gen.3:22 – 24), God was emotionally affected in a way that corresponds to Jesus’ human emotion and how he manifested it. To God, human death was preferable to immortalized sin, but that does not mean God ever took a detached, instrumentalist view of the human nature which was damaged and the human persons affected. Moreover, God had to protect Israel from attack and extermination, to provide a community in which Jesus could be born and interpreted, and therefore had to take some human life by gathering human souls in sheol/hades until Jesus could present himself to them (1 Pet.3:18 – 20; 4:6; Eph.4:9). But that does not mean God took an emotionally detached view of human life and experience of death. We should especially not attribute to God the desire to simply inflict pain as if He had a strictly retributive impulse in response to our wrongdoing and self-harm.

In Gethsemane, the Father ultimately willed the Son – or rather, the Father and Son shared one divine will – to manifest divine love for humanity – as in, everyone else’s humanity – by Jesus actively pressing onwards to make his own humanity what it ought to have been: a gift of new humanity to everyone else. Ultimately, the story of Gethsemane shows Jesus’ human struggle to align his human will with the fullness of the divine priorities.

And, Gethsemane indicates that the Father was empowering Jesus to carry through with dying and rising. Luke’s account includes the touching detail: ‘an angel from heaven appeared to him, strengthening him’ (Lk.22:43). Jesus agreed with the mission his Father gave him. He had to utterly defeat the corruption of sin that had lodged itself in his flesh. Only through death could he cut and burn it away, and perfect his human nature anew in resurrection power. In this radical mission to craft a new humanity for all humanity, ‘the Spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,’ in the disciples as in Jesus (Mt.26:41). Only then could Jesus share his Spirit of his new humanity with us. The conflict we see in Jesus therefore flowed from a collision of divine love from various directions – between his humanity at that moment and his humanity as it ought to be, and between his humanity at that moment and others’ humanity as it ought to be. This conflict between loves is an internal struggle worthy of the Triune God, a struggle which honors the incarnate Son and the Father who loves him, and us, deeply.

Would the Father Be Anything But Pleased by Jesus’ Conquest of Sin, and Lordship Over His Humanity?: Matthew 27:11 – 54

‘Which of the two do you want me to release for you?’ And they said, ‘Barabbas.’ (Matthew 27:21)

‘Truly this was the Son of God!’ (Matthew 27:55)

From the vantage point of the three mentions of the Father being ‘well-pleased’ with the Son, woven into the actual storyline of Matthew’s narrative, including the Gethsemane scene, we are in a better place to discern the presence and disposition of the Father during the crucifixion of Jesus.

Choosing Sons and Fathers

The immediate question posed by the narrative of Matthew was which ‘son’ will be chosen, and therefore which ‘father’ as well. Matthew portrays a deep irony. Jesus was rejected publicly and mocked for claiming to be the true ‘Son of the Father.’ Instead of him, the Jewish crowd chose Barabbas, a nickname which means ‘son of the father.’ The irony could not have been lost upon Matthew’s Jewish-background audience. The Jewish people present chose the wrong ‘son’ and therefore the wrong ‘father.’ The judgment they called down upon themselves, and rushed headlong into, was the selection of a military pretender to the messianic role. Barabbas was no mere thief, since Rome crucified failed revolutionaries and seditious zealots, not mere thieves. He was ‘a notorious prisoner’ (Mt.27:16), a military zealot, a failed revolutionary just like the others of that time period. Barabbas represented the road that many Jews would take as they would be led by their own wrongful interpretations of the Scriptures to attempt a war against the Roman Empire. In 70 AD, their attempt to liberate Jerusalem would fail. In 135 AD, the last holdout at Masada would fall to the Romans.

This particular wing of the Jewish community present at the crucifixion chose a different ‘father’ than the Father of Jesus. By opting to defend city and temple – which were destined to pass away based on biblical reasons they suppressed – by violent means, they removed themselves, at least for that time, from being able to name Abraham their father, too. By aligning against the Romans over the occupation of Jerusalem, they chose to neglect the original creational vision of God from Genesis 1, and God’s promise to Abraham in Genesis 12 to make of him a father of many nations. Some, in their militancy, may have reduced their faith community boundaries down to biological descent from Abraham, which would have been perverse because biblical Israel was always a multi-ethnic faith open to Gentile converts. In any case, Abraham, as ‘father’ of the faithful, was declared righteous by God (Gen.15) before he was circumcised (Gen.17), which indicated the possibility, at least, that the messianic family would be both Gentile and Jewish. And Moses used circumcision – itself a ‘new creation/new humanity’ motif in the journey of Abraham – as a motif of an even deeper, surgical healing, spiritually required by all humanity, provided by God (Dt.30:6) to mark the end of the exile. The Jews were fond of claiming Abraham as their father (e.g. Jn.8:39). But at this moment, were they Abraham’s children? The question of which ‘son’ and which ‘father’ were being offered could not have been more profound.

Is Barabbas an Example of Penal Substitution?

Many have speculated on whether there is a penal substitutionary symbolism involved with the choice of Barabbas and Jesus, the guilty and the innocent.[12] Poetic as that may be, up to a point, I do not think so.[13]

Jesus and Barabbas were both rebels from the perspective of the Roman Empire, and both were unapologetically guilty of that particular claim. So although Jesus was innocent from a moral perspective, he was not from a political one. When the Jewish crowd selected Barabbas, they showed that Jewish revolutionary fervor was agitated to such a degree that they would later accept a popular military leader without firm Davidic credentials. This would be additionally disastrous for the wider nation within one generation, and then another. To ignore this basic observation about the Jewish crowd’s selection of Barabbas is to also ignore Jesus’ many warnings to his contemporaries about the stark choice before them.

Moreover, the substitutionary element was not actually open to all. Jesus was crucified by the Romans because he claimed to be the ‘king of the Jews.’ The ordinary Jewish person did not and could not claim to be that king. The ordinary human person per se could not make that claim either.

Finally, the Old Testament critiqued Gentile empires in such a way that would in principle prevent Jesus and Matthew from casting Pontius Pilate or the Roman Empire in the place of God for the sake of atonement symbolism. That Old Testament critique of empire began with the critique of Babel in Genesis 11, and continued all the way through to Daniel’s beastly Gentile empires which distorted the good boundaries of God’s original creation. The book of Revelation would continue seeing Gentile empires as deformed creatures constructed from human collective sin (Rev.17 – 18). Jesus’ teachings were grounded in God’s original vision of creation, not an ethics of conformity to empires and pagan culture, which he critiqued not for their idolatry but for their abuse of power (Mt.20:25 – 28). His presentation of himself to the Jewish people and the Roman officials was therefore irreducible and conflictual on the most basic level. He was the heir to the throne of David, which was the throne of the world. So he came to call for Pontius Pilate’s surrender and confession of faith, not to make him a stand-in for God’s justice. Notably, Jesus will receive the Roman soldier’s when he breathed his final breath.

The Son Revealed the Father, in Unbroken Unity

The apparent silence of the Father at this point in Jesus’ life now makes sense. The Father did not need to split the sky again, or surround Jesus with a cloud of glory. The Father had already displayed his presence with Jesus, and love for Jesus, earlier in the narrative. The ‘well-pleased’ declaration from the baptism stressed Jesus’ victory over the corruption of sin in his humanity and the temptations that came with it (Mt.3:13 – 4:11). That declaration was an anointing for the kingship. The ‘well-pleased’ from the transfiguration stressed Jesus’ work of revealing himself through Davidic and temple motifs, and gathering a kingdom following (Mt.17:1 – 13). That ‘well-pleased’ was a more explicit commissioning for death and resurrection. If Jesus brought those threads to a climax at his crucifixion, why would the Father be anything but present and ‘well-pleased’ with the Son?

The Roman soldier’s confession serves to deepen the irony but punctuate the narrative with hope. Matthew makes a literary parallel between Simon Peter’s confession in Matthew 16:16 and the Roman soldier’s confession in Matthew 27:55.

Jewish: ‘You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.’ (Mt.16:16)

Gentile: ‘Truly this was the Son of God!’ (Mt.27:55)

This soldier, as a Roman, was used to confessing that Caesar was ‘the son of a god.’ For him to say that Jesus was ‘the Son of God’ meant something rather new and different. By speaking of ‘God’ and not ‘a god,’ he honored the Jewish story and the defiant Jewish monotheism that picked fights with the polytheism of Egypt, Canaan, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. That by itself was remarkable. By saying that Jesus was ‘the Son’ of this God meant that God the Father was well-represented by Jesus. When Christians called Joseph ‘Barnabus’ (Acts 4:36), they called him ‘son of encouragement’ because ‘encouraging’ (nabus) was such a strong characteristic of Joseph that he was called a ‘son’ (bar) of that quality. In Jesus’ case, the transitive property of identification goes in the other direction. For Jesus to be called ‘the Son’ of God the Father means that the one true Father was characterized by Jesus. The revealed must characterize the hidden. If the Son is able to suffer with composure and integrity while innocent, then the Father must be of the same character and love.

If we say with Jesus that the Son reveals the Father, and if we say with the Roman soldier that Jesus was and is the Son of God, the God of Israel, then we are drawn by the logic to a conclusion. The Father was revealing his character through the Son all throughout the crucifixion experience. ‘Well-pleased’ as he was with his Son, the Father did not turn against or away from the Son. This Roman’s confession – though admittedly a small piece of evidence in the overall case – adds another element to the logical and literary argument that penal substitution is not based on the biblical text, but is a foreign intrusion into it. The Father was revealing himself in and through the Son, for the Son was choosing to reveal him (Mt.11:27).

Thus, Jesus offered everyone watching him a glimpse of the Father, through his own life, as his Father’s unique Son (Mt.11:25 – 27). He was not aligning God the Father with the Roman Empire and the hierarchies of power that men (and occasionally, women) set up. He was not aligning God the Father with hopeless and desperate rebellions, either. He was, rather, aligning God the Father with himself as he embraced our humanity out of covenant love, as he loved those who were enemies. Jesus was representing God the Father as being the truly rejected and exiled one, in and through his own experience of being rejected. He was aligning God the Father with his personal claim of love for every human being, claiming them for a family and a kingdom that broke boundaries, gathered under his own lordship as king. Perhaps he was aligning God the Father with his own silence from the cross (when he was silent), because it represented the Father’s divine emotion (grieving the Holy Spirit – Eph.4:30) for humanity’s waywardness. Jesus was representing God the Father as the one who still calls us to put to death the corruption of sin within our human nature, with trust that the Father will empower us by his Spirit and pull us through into resurrection life. And Jesus was representing his Father as the one who gives us that victory and restoration as a gift, because Jesus was giving himself to accomplish it on behalf of all the Father’s beloved ones. Jesus revealed God the Father as the one who dignifies our stories within his larger story, because he gave his Son to retell our stories but better. Jesus showed that he is the true ‘Son’ of the true ‘Father.’ As he said before, he alone truly revealed the Father. Throughout the crucifixion, the Father was present with Jesus, being ever and always for Jesus, having only love for him.

The Continuity of the Father’s Blessing on the Son and Presence With the Son

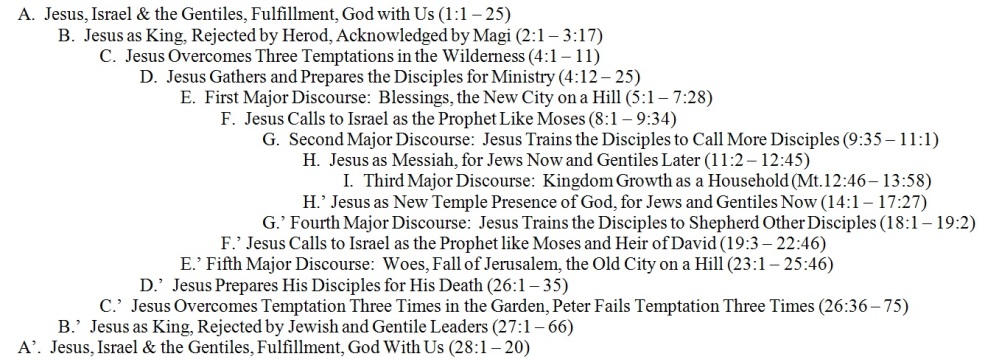

In addition, if I am correct in perceiving a literary chiasm running through Matthew’s Gospel as a whole, then the Father’s pleasure in the Son, and presence with the Son, must be maintained, if not enhanced, by the episode of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Some chiastic structures are thematic inversions. That is, in chiastic structures where the central point brings about a sharp change in the direction of the story, the plot elements after the center point are reversals of the points made earlier. An example of this pattern would be the younger son in the parable of the two lost sons (Lk.15:11 – 24).

Other chiastic structures are thematic amplifications. That is, the central point brings about an increase or amplification of what happened to that point in the story. So the plot elements after the center point are amplifications of the points made earlier. An example of this pattern would be the older son in the same parable, above (Lk.15:25 – 32).

The chiastic structure of Matthew is a thematic amplification. The points in the latter half of the narrative amplify the points in the earlier half. I have made available my detailed outline of the chiasm as I perceive it.[14] But for now, I will make a few specific comments based on summaries of the major chiastic points.

Section A (Mt.1) is amplified by Section A’ (Mt.28)

- The four Gentile women converts who entered the genealogy of Jesus via marriage anticipates the full Gentile inclusion brought about by Jesus’ mission to the world (Mt. 1:1 – 17; 28:16 – 20).

- Jesus’ lineage as heir of David is filled full and amplified by his realization of the full Davidic, royal ‘all authority’ given to him by the Father.

- The dilemma of Israel’s exile (Mt.1:11, 17) is resolved by Jesus rising from the dead, which means that the Father has restored him from the greater exile (Ezk.37).

- The angel’s appearance to Joseph in a dream (Mt.1:20 – 21) is amplified by an angel’s actual appearance by the empty tomb (Mt.28:6).

- The prophetic expectation fulfilled by Jesus’ birth (Mt.1:22 – 23) is amplified by the fulfillment of Jesus’ own prediction (Mt.28:7).

- And the birthname of Jesus, Immanuel meaning ‘God with us’ (Mt.1:23) is filled full by Jesus’ personal presence with his disciples in mission: ‘Lo, I am with you always’ (Mt.28:20).

Section B (Mt.2:1 – 3:17) is amplified by Section B’ (Mt.27:1 – 66).

- Resistance to the infant Jesus from one ruler, King Herod (Mt.2:1ff.) is amplified into resistance to the adult Jesus by both Jewish and Roman rulers (Mt.27:11 – 54).

- The titles ‘king’ or ‘messiah’ occurs while he is a baby (Mt.2:2, 4), while the titles ‘king of the Jews,’ ‘king of Israel,’ and ‘son of God’ are used for him as an adult (Mt.27:29, 36, 40, 42, 43, 54).

- Jesus fills to the full messianic prophecy about his birth (Mic.5:2 in Mt.2:6; likely the star refers to Num.24:17), and fills to the full messianic prophecies about his death (Isa.53:12 is triggered in Mt.26:56; Isa.53:9 seen in Mt.27:4, 19, 23, 54; Isa.53:7 seen in Mt.27:13 – 14; Isa.53:9 seen in 27:38 and 57 – 60).

- As a baby, Jesus begins to retell Israel’s story (descent to Egypt and return in 2:13 – 23, fulfilling Hos.11:1 and Num.24:8), while the adult Jesus fills to the full Joseph’s story, betrayed by ‘Judah’ for silver into exile (Mt.27:1 – 10), and David’s pre-enthronement story of rejection and hardship (Ps.22:1 in Mt.27:46).

- Gentile magi-kings honor the infant Jesus as king and worship him (Mt.2:11), which is amplified by the Roman soldier who participates in Jesus’ crucifixion and yet honors Jesus as ‘Son of God’ (Mt.27:55).

- Most significantly, the baptism of Jesus (Mt.3:13 – 17) – his symbolic dying and rising – parallels his actual dying and rising in his death and resurrection (Mt.27:52ff.).

The amplification of motifs from A to A’ and from B to B’ strongly suggests continuity, not discontinuity, specifically on the question of the Father’s disposition towards the Son while Jesus was on the cross. In other words, if at Jesus’ baptism, when Jesus declared his commitment to rid his human nature of the corruption of sin, God the Father said he was ‘well-pleased’ with his Son, what possible reason would the Father, at Jesus’ climactic victory over that corruption, be other than ‘well-pleased’? To claim, as John Stott and other penal substitution advocates do, that the Father was ‘ill-tempered’ with the Son on the cross, has absolutely no literary basis in the text.

The Father’s quotation of Psalm 2:7, ‘You are my Son,’ from the coronation song spoken over the kings of Judah, parallels Jesus’ own use of Psalm 22:1, which is Jesus’ confident claim to the throne of David. His confidence was based on his consistent, lived parallel to the pre-enthronement life of David, the hunted king in the wilderness. And since this literary parallel between Psalm 2 and Psalm 22 seems compelling, even without the weight of the chiasm behind it, then I once again propose that the anointing of the Holy Spirit in Jesus’ baptism and blessing of the Father must have been the constant reality in Jesus’ life, without exception. If David never lost his anointing to be king, then we can say with confidence that Jesus never lost the Father’s favor and his anointing to be king, either, and his anointing was in fact the Spirit of God. What does a penal substitution advocate say the Holy Spirit was doing at that moment when the Father supposedly turned against or away from the Son? I have not found anyone who approaches that question.

The Trinitarian disclosure of Father, Spirit, and Son revealed in Jesus’ baptism was not momentary. Quite to the contrary, it was the hidden, spiritual stability throughout Jesus’ entire life, including at the cross. It follows that Jesus never faced a closed, silent heaven. At every moment on the cross, and especially as he was finally putting to death the corruption of sin lodged in his human nature, Jesus heard the blessing of his ever-constant, ever-loving Father, as always: ‘This is My Son, in whom I am well pleased.’ Jesus’ parallel declaration to others was, ‘Like David was, I am the hunted king in exile, suffering, but on my way to the throne.’

In both episodes surrounding the quotations of Psalm 2 and 22, Jesus’ identity as Son of the Father, anointed by the Spirit from the Father, was sorely tested, but vindicated. His baptism served as a foreshadowing of his death, burial, and resurrection; this affirmation and anointing of Jesus was followed by the wilderness temptation, during which Jesus affirmed his identity as Son of the Father. The temptation in the garden of Gethsemane (Mt.26:36 – 75) serves as the other bookend corresponding to the wilderness. Jesus struggled in three categorical ways during his temptation in the wilderness; he also struggled three times during his temptation in Gethsemane. Simon Peter and the other disciples succumbed to temptation three times in Gethsemane, which served as a contrast with Jesus’ faithfulness to pray and prepare himself for the trial to come. His actual death, burial, and resurrection awaited him the next day. This was the reality to which his baptism pointed. The cross, then, was the climactic moment where Jesus’ identity as Son of the Father, anointed by the Spirit from the Father, was sorely tested, but vindicated. So the Father’s quotation of Psalm 2 is answered by Jesus’ quotation of Psalm 22. This means that the Jewish kingly title ‘Son of God,’ which was defined and applied to Jesus at the cross, can now be coordinated with the baptismal title ‘Son of God,’ which was declared at the Jordan River when Jesus disclosed the Holy Trinity.

In other words, the one who was always the ‘Son of God’ in one sense became the ‘Son of God’ in another sense. That is, the ‘Son of God,’ meaning ‘the eternal Son in unending fellowship with the Father and the Spirit’ in the sense of the Nicene Creed, fully accomplished the work of the ‘Son of God’ meaning ‘king of the Jews,’ a role carved out for him by the biblical narrative, defeating the deepest enemies of God, constructing a new holy temple for God in his own humanity, and delivering his people from bondage to sin by sharing his Spirit with them. Jesus Christ on the cross is the precise moment when this title, ‘Son of God,’ can be invested with both meanings. Christ understood as ‘Son of God’ in both senses at the cross anchors the overlap of dogmatic creedal theology and biblical studies. The eternal Son, now-incarnate, hung on the cross, while still knowing and experiencing the unending and unbroken fellowship with the Father and the Spirit. In this explanation, contra Stott, we founder on no rational inconsistencies and ‘paradoxes’ (contradictions) about the Father-Son-Spirit relation. If the cross and resurrection was when the eternal Son of God became the kingly Son of God, it follows that the Father, who constitutes Jesus’ Sonship in both senses, was always present with him by the Spirit. In short, if we call Jesus the Son, then we acknowledge the Father who is with him, too.

Conclusion

As I mentioned before, John Stott’s argument goes awry because he assumes that Jesus’ quotation of Psalm 22:1 has to do with Jesus’ humanity in a generic sense, rather than a specifically Davidic sense. Stott remarks:

‘Jesus had been meditating on Psalm 22, which describes the cruel persecution of an innocent and godly man, as he was meditating on other Psalms which he quoted from the cross…’[15]

Stott should have recognized that the decisive factor is not Jesus’ humanity per se but his specific, kingly, Davidic role within Israel and the world. That is, Jesus’ humanity took its particular shape because of the role he played as the human descendent of King David on Mary’s side (Lk.3:23 – 38), and as a claimant to the Davidic throne on Joseph’s side (Mt.1:1 – 17). For Jesus was the Son of David who was the greater David. He was not simply human in a general, generic sense as if his social location in Israel and his familial position as the eldest son of Mary and Joseph didn’t matter. Even Jesus’ meditations on the Psalms from the cross were not accidental: The reason why Jesus meditated on, and evoked, the first of five portions of the book of Psalms was because he was following in the path of hardship and rejection marked out for him by David in his journey to enthronement.[16] For reasons I explained earlier about the entire structure of the Book of Psalms as the history and future of the house of David, I think it is quite likely that Jesus was especially reflecting on Psalms 22 – 31, if not the entire first portion of the Book of Psalms, Psalm 1 – 41.

Stott’s suggestion, that Jesus’ experience on the cross is a mirror to us of our ordinary human experience of feeling forsaken by God, is oriented incorrectly. Jesus’ experience is a mirror to us of our human experience of feeling forsaken to enemies, or vulnerable to threatening forces, while still having confidence of the Father’s watchful love (e.g. Ps.34:6 – 7). Understood this way, Jesus indeed encourages us by participating in our sufferings. He makes a way through them, for us. And Jesus did so while always knowing the Father’s love. With him, by the Spirit, we too know the unbroken and unshakable love of the Father.

[1] John R.W. Stott, The Cross of Christ (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1986), p.81

[2] Ibid p.81 – 82

[3] Ibid p.74 – 75

[4] Ibid p.76 – 77

[5] See my list of resources and citations from the patristic period here: http://www.anastasiscenter.org/gods-goodness-fire.

‘Fire’ is God’s attempt to refine and purify people. When God closed the garden to Adam and Eve, the first incidence of fire anywhere in Scripture occurs. Guarding the way to the tree of life was a flaming sword (Gen.3:24), probably symbolizing the word of God (Rev.1:16, etc.) which can cut /burn uncleanness away. Both the fire motif and the sword motif anticipate circumcising/cutting/burning something away from people so they could eventually return to the tree of life. Critical to this motif is the teaching of the Pentateuch about human nature. The early church had a very strong understanding of human nature from a biblical perspective. Adam and Eve damaged and cursed human nature by taking in the power and desire to define good and evil for themselves (Gen.3: 1 – 7). The damage was further shown by the fact that their son Cain did not need an external voice to make him jealous. The voice was already internal to him; sin was crouching at his door within him. By murdering his brother, Cain damaged his own human nature even further, explicitly cursing himself so the land would not be fruitful for him (Gen.4:11). But God called for our human partnership to burn and/or cut something away our human nature – with each person, because God in His love made us with the capacity to shape our human nature with Him.

The theme of the sword-circumcision complements the theme of fire. God instituted circumcision (Gen.17) with Abraham and Sarah, as a new kind of Adam and Eve in a new garden land, after they learned to ‘cut away’ certain attitudes of male privilege and power which were culturally but not spiritually acceptable; God wanted them to have a child like Adam and Eve would have had a child, with hope and trust in Him; Abraham could not discard Eve and monopolize the promise for himself (Gen.12); Abraham could not name a non-biological heir (Gen.15); Abraham and Sarah could not use a surrogate mother (Gen.16). God used circumcision as a symbol that He and they had ‘cut away’ something unclean from their attitudes about marriage and parenting. Circumcision was institutionalized with all male children of Israel to show how the covenant ‘cut away’ something unclean from humans (Lev.12), and later was used as a outward symbol of an inward surgery where God and humans in partnership would ‘cut away’ something unclean from the human heart by the Law being written on the heart (Dt.10:16; 30:6).

God then appears as a fire in the burning thorn bush (Ex.3:2; Acts 7:30). God also appears as fire on Mount Sinai inviting Israel higher up and further in (Ex.19:13; Dt.5:5). See also Hebrews 12:18 – 29, where the writer says that we come not to the fiery Mt. Sinai, but to a new Mt. Zion after having been cleansed and perfected through Jesus, ‘for our God is a consuming fire.’ And God in Israel’s Temple was acting like a dialysis machine: ‘Give me your impurity, and I will give you back My purity.’ It was like Jewish circumcision, cutting something unclean away from the person, and cleansing the person. The laying on of hands on the animal symbolized placing the corrupted part of us and giving it to God to consume. God consumed it with fire directly, or indirectly consumed it through the priests. God then gave Israel back innocent, uncorrupted animal blood. So God used the sacrifices as a way of refining and purifying Israel.

[6] For more information on these New Testament passages on fire and darkness, as well as the Old Testament’s treatment of these motifs, see my paper, Hell as Fire and Darkness: Remembrance of Sinai as Covenant Rejection in Matthew’s Gospel found here: http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/matthew-theme-fire-and-darkness-as-hell.pdf. And also an exploration of systematic theology, church history, and Scripture in Hell as the Love of God found here: http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/article-hell-as-the-love-of-god.pdf.

[7] See Mako A. Nagasawa, Hell as the Love of God found here: http://newhumanityinstitute.org//pdfs/article-hell-as-the-love-of-god.pdf. See also Steve McVey, What is God’s Wrath? (Grace Communion International), found here: https://www.gci.org/YI112

So is fire positive or negative for us? If we want to be cleansed by Jesus’ Holy Spirit, fire is positive. The Spirit refines us like precious metal in fire. The Spirit took Jesus’ humanity and empowered him to resist temptation (Mt.3:13 – 4:11). Which meant Jesus was baptized by the Holy Spirit to purify his human nature. He then said that his presence was giving forth ‘light’ in darkness as Isaiah prophesied (Mt.4:16). His followers would become the new temple-presence of God; they would be like a lamp, which of course gives off light by a burning fire within (Mt.5:14 – 16), because they would participate in Jesus’ own purification of his human nature. In each of us, our spiritual eye’s focus serves as a lamp, which lights us within (Mt.6:22 – 23). Very importantly, the next time the Spirit’s presence is manifested on Jesus, the Spirit transfigures him (Mt.17:2, 5), and presents Jesus as the new temple-presence of God on a mountain, engulfed in the divine glory-cloud. Like at the baptism of Jesus, the Father and the Spirit acknowledge Jesus’ identity publicly, and this literary symmetry is important because it establishes the ‘Spirit and fire’ baptism that Jesus is putting his human nature through, by which he gives forth light through his very own humanity. The parable of the ten virgins uses the motifs of the lamp, oil, fire, and light to represent our inward preparation to contribute to a kingdom celebration much bigger than ourselves (Mt.25:1 – 13). If not, fire is negative, destructive. But it depends on us. The same is true in Jesus’ use of ‘fire and darkness’ as a conjoined motif throughout the Gospels. He was reminding people of Israel’s refusal to go up Mount Sinai and be purified by God. God then appeared to them, from the outside, as ‘fire and darkness.’ But for Jesus’ disciples, at Pentecost, the Spirit comes with tongues of fire upon them (Acts 2:1 – 13), symbolizing purification.

Revelation uses fire as symbolic of God’s refining presence. Jesus is described first with fire. ‘His head and His hair were white like white wool, like snow; and His eyes were like a flame of fire. His feet were like burnished bronze, when it has been made to glow in a furnace’ (Rev.1:14 – 15; 2:18). He says, ‘I advise you to buy from Me gold refined by fire so that you may become rich, and white garments so that you may clothe yourself, and that the shame of your nakedness will not be revealed; and eye salve to anoint your eyes so that you may see.’ (Rev.3:18). But then, fire is destroying for those who cling to impurity: ‘tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb’ (Rev.14:10). And of course we have the famous lake of fire passage (Rev.20:12 – 15). But the followers of Jesus are purified as ‘pure gold, like clear glass’ (Rev.21:18, 21). Pure gold is not like clear glass in terms of transparency. But pure gold is like clear glass in terms of being purified of any impurity. So when God is described as fire, the Bible pairs that description with the effect of fire: either purified people, or tormented people.

[8] Edward T. Oakes, S.J., Infinity Dwindled to Infancy: A Catholic and Evangelical Christology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011), p.165

[9] Emptiness to joy: Water into wine at Cana (Jn.2:1 – 10). Sickness to health: Healing of the royal official’s sick son (Jn.4:46 – 54). Debilitation to wholeness: Healing the invalid man (Jn.5:1 – 15). Hunger to nourishment: Multiplication of bread (Jn.6:1 – 14). Fear to peace: Walking on water (Jn.6:16 – 21). Blindness to sight: Healing of the blind man (Jn.9:1 – 41). Death to life: Resuscitation of Lazarus (Jn.11:17 – 44).

[10] I am the bread of life (Jn.6:35). I am the light of the world (Jn.8:12). I am the door (Jn.10:7). I am the good shepherd (Jn.10:11). I am the resurrection and the life (Jn.11:25). I am the way, the truth, and the life (Jn.14:6). I am the true vine (Jn.15:1)

[11] The ‘new birth’ discourse with Nicodemus (Jn.3:1 – 21). The ‘living water’ discourse with Samaritan woman (Jn.4:1 – 42). The Father-Son discourse (Jn.5:16 – 45). The ‘bread of life’ discourse (Jn.6:22 – 71). The ‘descent from Abraham’ debate with the Pharisees (Jn.8:12 – 59). The ‘good shepherd’ discourse (Jn.10:1 – 38). The ‘Upper Room’ discourse (Jn.13:1 – 17:26).

[12] Perhaps the most interesting of the theories come from N.T. Wright, who suggests that if there is a penalty that Jesus substituted himself in for, it would be the penalty he suffered at the hands of the Romans for claiming to the ‘king of the Jews.’ From this bedrock of historical fact, Wright suggests that some form of ‘penal substitution’ can be re-conceptualized and re-historicized. For, it would seem that Jesus took the penalty of death for his followers, whom he instructed specifically not to participate in the Jewish attempt to liberate Jerusalem from Rome (e.g. Mt.24:1 – 31). Christians, therefore, escaped the bloodbath of 70 AD because Jesus ‘substituted’ himself in for them, as their king. Remarkably, Trevin Wax, Don’t Tell Me N.T. Wright Denies “Penal Substitution”, (The Gospel Coalition, April 24, 2007), a leading contributor to The Gospel Coalition, an organization dedicated to equation of ‘penal substitutionary atonement’ with ‘the gospel,’ praised Wright in a 2007 article. Wax offers that Wright should be credited with maintaining penal substitutionary atonement. Hence the title of his own article, which is found here: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/trevin-wax/dont-tell-me-nt-wright-denies-penal-substitution/.

[13] I believe Wright, for his part, was mistaken that ‘penal substitution’ can be re-centered around the events of 70 AD. I do not see how the historical facts of the Jewish-Roman War polarity can somehow be projected into the character of God by some disciplined philosophizing or allegorizing. Nor can Pontius Pilate represent God. Nor can Jesus be the penal substitute for the everyday Israelite, because Israel was already suffering exile. Jesus took the Roman punishment of crucifixion precisely because he wore the mantle of ‘king of the Jews.’ The ordinary Jew did not and could not claim to be that king.

Referring to the footnote above: Trevin Wax does not seem to grasp the significance of how Wright shifts the target of God’s wrath from Jesus’ personhood to the corruption of sin within Jesus’ human nature, which makes Jesus’ self-substitution fundamentally not penal. Wax is mistaken, furthermore, because Wright had been diplomatically vague until he took the subject of atonement head on in his 2016 book The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’ Crucifixion.

Also, Wax does not pay close enough attention to how Wright describes the Sinai covenant. Wright perceives the Sinai covenant as founded on God’s restorative justice, and expressing it, and explicitly denies that it portrays or enacts God’s supposedly retributive justice, which is a foundational point for penal substitution. N.T. Wright, Evil and the Justice of God (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), p.64 says,

‘If you want to understand God’s justice in an unjust world, says the prophet Isaiah, this is where you must look. God’s justice is not simply a blind dispersing of rewards for the virtuous and punishments for the wicked, though plenty of those are to be found on the way. God’s justice is a saving, healing, restorative justice, because the God to whom justice belongs is the Creator God who has yet to complete his original plan for creation and whose justice is designed not simply to restore balance to a world out of kilter but to bring glorious completion and fruition the creation, teeming with life and possibility, that he made in the first place. And he remains implacably determined to complete this project through his image-bearing human creatures and, more specifically, through the family of Abraham.’

See also p.73. Wright, The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’ Crucifixion (New York, NY: Harper One, 2016), p.275 is more specific, complete with Wright’s back-handed humor:

‘According to some, God gave the law in order to terrify people with the prospect of judgment, so that they would run to the gospel for relief. That appears to make some sense, provided you approach the whole thing from the works-contract point of view. But this is not, however, the sense Paul had in mind.’

[14] See Mako Nagasawa, The Chiastic Structure of the Gospel of Matthew, found here: http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/matthew-chiasm.pdf

[15] John Stott, The Cross of Christ (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1986), p.82

[16] While on the cross, Jesus quoted Psalm 22:1 (Mt.27:45; Mk.15:34 – 35) and Psalm 31:5 (Lk.23:46). Perhaps Psalm 22:15 should be seen as contributing to John 19:28.